Nicholas Kristof Highlights Helen Keller International

This op-ed originally appeared in the Sunday Review Section of the April 5, 2015 edition of The New York Times.

The Trader Who Donates Half His Pay

Matt Wage was a brilliant, earnest student at Princeton University, a star of the classroom and a deep thinker about his own ethical obligations to the world. His senior thesis won a prize as the year’s best in the philosophy department, and he was accepted for postgraduate study at Oxford University.

Instead, after graduation in 2012, he took a job at an arbitrage trading firm on Wall Street.

You might think that his professor, Peter Singer, the moral philosopher, would disown him as a sellout. Instead, Singer holds him up as a model.

That’s because Wage reasoned that if he took a high-paying job in finance, he could contribute more to charity. Sure enough, he says that in 2013 he donated more than $100,000, roughly half his pretax income.

Wage told me that he plans to remain in finance and donate half his income. One of the major charities Wage gives to is the Against Malaria Foundation, which, by one analyst’s calculation, can save a child’s life on average for each $3,340 donated. All this suggests that Wage may save more lives with his donations than if he had become an aid worker.

“One thought I find motivating is to imagine how great you’d feel if you saved someone’s life,” Wage says. “If you somehow saved a dozen people from a burning building, then you might remember that as one of the greatest things you ever did. But it turns out that saving this many lives is within the reach of ordinary people who simply donate a piece of their income.”

Hm. Wage may be the only finance guy who I wish could be paid more!

Wage is an exemplar of a new movement called “effective altruism,” aimed at taking a rigorous, nonsentimental approach to making the maximum difference in the world. Singer has been a leader in this movement, and in a book scheduled to be released in the coming week he explores what it means to live ethically.

The book, “The Most Good You Can Do,” takes a dim view of conventional charitable donations, such as supporting art museums or universities, churches or dog shelters. Singer asks: Is supporting an art museum really as socially useful as, say, helping people avoid blindness?

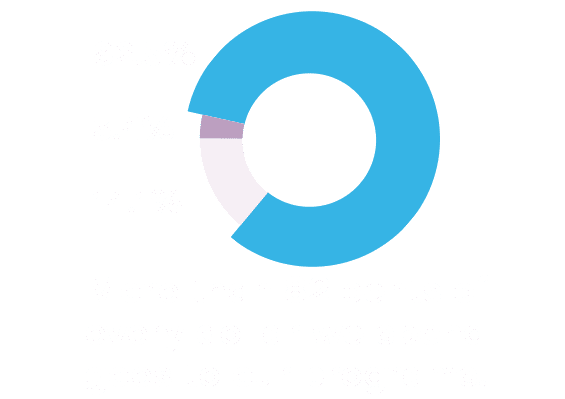

After all, an American aid group, Helen Keller International, corrects blindness in the developing world for less than $75 per patient. It’s difficult to see how a modest contribution to a church, opera or university will be as transformative as helping the blind see again.

Even though he’s one of the founders of the field of animal rights, Singer is skeptical of support for dog rescue organizations. The real suffering in the animal world, he says, is in industrial agriculture, for there are about 50 times as many animals raised and slaughtered in factory farms in the United States each year as there are dogs and cats that are pets in America. The way to ease the pain of the greatest number of animals, he says, is to focus on chickens.